Monday, May 11, 2020

Remembering WWII nurses.

National Nurses Week begins each year on May 6, the day that Florence Nightingale, the founder of professional nursing, went to the Crimean War as a nurse in 1853, and ends on her birthday – May 12. During this week we acknowledge the excellence and dedication of those who choose the nursing profession. I grew up surrounded by nurses in a nursing home in Old Mystic, CT that my family owned and operated in the 1950s. My mother’s skills as a Registered Nurse also made her the go-to person for many emergencies around the village – cuts, burns and even broken bones, head injuries and emotional problems. Injured people would show up at the nursing home, like they do today at emergency rooms, except that she received no compensation other than the occasional basket of eggs or leg of lamb that might arrive later.

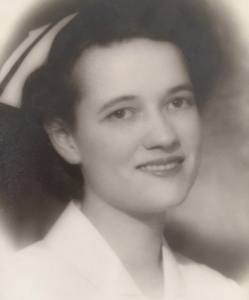

My mother, Estella Ashcroft Whipple, in 1943

I can still see my mother rushing from the bedside of an elderly person and calmly cleaning and dressing someone’s bloody wound after an accident down the street. On another occasion, I remember her carefully positioning a child’s possibly broken leg after a fall from a tree. Eventually, Dr. Ryley or Dr. Fowler would arrive from Mystic, but watching my mother and her nurse colleagues in action, day after day, offered me firsthand knowledge that nurses were the unsung heroines. They were the first responders in the old days.

Nurses in war zones and military settings also did their job quietly and largely unnoticed, putting their lives in peril on the battlefield for centuries. Yet, little is known about their experiences in war or exactly how many participated. Even appropriate financial remuneration in the nursing profession has been meager and long in coming. Only at the end of the twentieth century did nurses’ pay, both in military and civilian life, begin to become commensurate with the risks and responsibilities of their jobs.

Many women served as nurses during the Revolutionary War, but they are barely mentioned in history books. The Second Continental Congress, heeding George Washington’s advice to establish a means of caring for wounded and sick soldiers, authorized the formation of hospitals. In July of 1775, congress initiated a plan to provide one nurse for every ten patients and a supervising matron for every ten nurses. But nurses were not always easy to find and formal training was nonexistent. General Washington blamed the low compensation rate—originally $2 a month—for the shortage of nurses. It’s more probable that a woman risked receiving a bad moral reputation in those days if she wanted to be a nurse. Congress did increase nurses’ pay a year later, in 1776, to $8 a month.

Louisa May Alcott, long before writing Little Women, had a brief career as an army nurse during the Civil War. Her first publication, Hospital Sketches, was a detailed account of her experiences. Louisa was an unknown but zealous patriot from Massachusetts when she arrived in Washington, DC, in 1862, to work in the Union Hotel Army Hospital. She had read Florence Nightingale’s Notes on Nursing and Dr. Home’s Report on Gunshot Wounds, but that was the extent of her training. She described in letters to her family that, on her first day, “…stretcher after stretcher arrived from the battle of Fredericksburg…each with a legless, armless or desperately wounded occupant.” Louisa cared for hundreds of soldiers with devastating wounds and loss of limbs, working with little more than soap, water, and whiskey. (Hospital Sketches is available at the Mystic and Noank library)

Her descriptions were so vivid and evoked so much emotion about caring for the wounded, that the Union Army published her book and provided it to the families of soldiers. This small volume established her reputation as an author but her experience devastated her health. She contracted Typhoid Pneumonia after six weeks and would suffer from the poisonous effects of treatment with mercury until her death in 1888.

She reported in her journal that she was pleased to receive ten dollars for her short stint in Washington, revealing that nurses’ pay had barely improved in one hundred years since the Revolutionary War. Approximately 6000 women served as nurses during the Civil War and their reward was largely the legacy of gratitude described in the letters and journals of the wounded.

Fifty years later, in 1901, the Army Nurse Corp was created during the Spanish-American War and nurses were appointed to work for three years but were not commissioned as army officers. The appointment could be renewed if their skills were satisfactory, but it would take two more wars and another fifty years for nurses to receive commissioned officer status in 1944.

I am on this earth because of the compassion of nurses. During World War I, my grandfather, George Ashcroft, served in the British Army and ended up in a hospital in Malta after suffering the effects of mustard gas and severe wounds in France. The nurses suggested that he correspond with someone. He remembered a young woman, Jenny Whipple, he had met on a farm in Connecticut years before. The letters commenced and they married on his return, eventually creating my mother.

Growing up around nurses in the 1950s I was privy to occasional stories and vivid memories. One former army nurse would sit with me and my brothers at a picnic table during her break-time and launch into stories. She once described being one of sixty nurses, climbing over the side of a ship off the coast of North Africa and down an iron ladder into small assault boats where they waded ashore and huddled behind a sand dune while enemy snipers took potshots at them. We had no idea that we were listening to a first-person account that was rarely preserved for posterity.

Nurses were not spared capture and imprisonment during war. In 1945 U.S. troops liberated sixty-seven army nurses who had been imprisoned since 1942 in the Santo Tomas Internment Camp in the Philippines. They were evacuated to a convalescent hospital on Leyte where they recovered from malnutrition. Like other veterans who saw the worst of war, these women came home and slipped back into their communities and seldom shared their experiences.

The exact number of nurses who served in World War II is unknown, but they received 1,619 medals, citations, and commendations.

During the Korean War, Army nurses served in medical units close to the front lines, in field hospitals, on army transport ships, hospital trains and at MASH units (Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals). By chance, the general public has more knowledge of military nurses thanks to popular culture. The fictionalized depiction of a medical unit portrayed in the film, MASH, in 1970, and a subsequent TV series featuring “Hot Lips” Hoolihan, offered a romanticized version of women nurses in wartime – but, at least it showed that they were there.

During the Vietnam War, on November 8, 1967, all restrictions to female officer careers were removed. Finally, members of the Women’s Army Corps and the Army Nurse Corps could receive the same promotions as those applied to men. Col. Anna Mae Hays achieved the rank of brigadier general on June 11, 1970. Again, the exact number is not known, but thousands of women served as nurses in Vietnam. The number killed in Vietnam is also unclear, ranging from seven to nine.

Nurses have served in untold numbers in wartime, even before Florence Nightingale went to the Crimean War and became known as “the lady with the lamp.” I’m comforted by the thought that nurses were near the battlefields of Vietnam in 1969 to care for my husband in the brief moments he survived after being mortally wounded in a booby-trapped bunker. I may never know who they are, but I’m sure they eased his death with calm and compassion. I’m deeply grateful for all those who choose to be nurses and medics.

Thank you to nurses everywhere – this week and every week – for all you do.