Tuesday, January 9, 2024

There Dwells a Sect With More Millions Than Members.

Of the Thousand Who Followed George Rapp to America in 1805 Eighteen Now Remain—They Think the World Will End Before the Last of Them Dies—Quiet and Simple Life in a Pennsylvania Village.

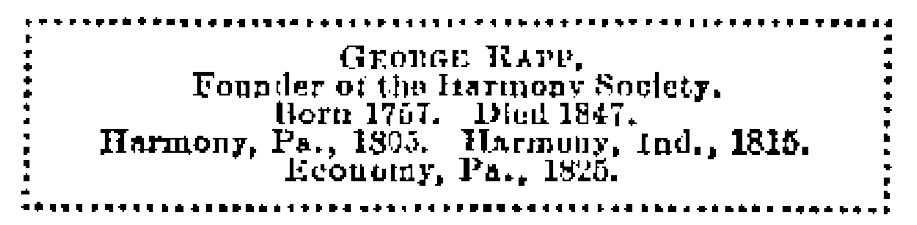

Economy is the quaintest village in the United States. It is situated on the Fort Wayne Railroad, eighteen miles below Pittsburgh, yet it is as unlike an American town as if it belonged to another part of the globe. Neither the bustle of the nearby city nor the railroad and steamboat lines ever penetrate the heart of the sleepy town. It is the home of the Economites, a society founded by George Rapp in Germany many, many years ago. What all their beliefs were is more than any outsider can ever tell. Their chief aim was to live as the earliest Christians did, as portrayed in the writings of the apostles. Driven from Germany by religious persecution, they emigrated to America in 1805 and settled in Pennsylvania.

They bought land and built a village which they called Harmony. They dubbed themselves Harmonites, and gave what earthly goods they possessed to their founder and leader, George Rapp, who was their father, banker, adviser and preacher.

At first the members married with the understanding that they were only to live together for a few months every seven years. After several had broken this law, and among them Rapp’s own son John, George Rapp decided that it would be more in conformity with the teachings of the disciples to live a life of celibacy. Several of the members who had wives and sweethearts rebelled against this. They were all formally ordered to appear before their leader, where they were told to give up their love and their wives or to renounce the society. Those who were true to Rapp moved with him to Indiana, where another Harmony was founded. Disease attacked the new village and reduced the number of its inhabitants so greatly that the remaining ones fled back to Pennsylvania. In 1825 they bought 2,500 acres of land in a most beautiful valley near Pittsburgh. Here they settled and here those of them who are still alive, live to-day. The misfortunes that befell them in the two Harmony settlements caused them to change the name. They called their new home Economy and themselves Economites. The members who deserted the Harmonites either died out or became as other citizens of the globe. Many of their descendants are well-known people in and around Allegheny City.

The Eighteen Who Survive.

The Eighteen Who Survive.

About one thousand members first settled in Economy, but as their number was never increased by birth or by adoption, and as death occasionally invaded their homes, there remain at the present time not more than eighteen members, the youngest of whom is sixty-two years old. When they first took vows of celibacy they believed that the world was nearing its end, and so they lived simple lives, preparing for the mysterious hereafter. George Rapp, just before he died, told the others the world would surely end before the last member died. They believe it.

On entering the village one sees plain houses, wide, well-kept streets, lined on either side with large shade trees and chickens—nothing else. It is a most unusual sight to see any people on the streets. The thrifty appearance alone prevents a visitor from thinking it a deserted village or imagining that the inhabitants were awaiting the Prince’s arrival to awake them from a century-long sleep. The houses are all alike. They are all built with the gable end towards the street and cannot be entered except through the yards. There are no front stoops to fall over in Economy. Grapevines are trained to cover the street side of all the houses, but they are pruned so as not to interfere with the light of the windows. I imagine it would be pleasant to sit at one of those windows during grape seasons.

The men are housekeepers, and so are the women. They never mingle, not even at work. The dress of one is the dress of all. Everything is on an equality. The men wear blue broadcloth long-tailed coats, wide trousers and broad-brimmed black hats. On holidays the broadcloth is exchanged for blue silk attire. The women wear straight, full skirts, gathered on a plain waist of blue flannel, gingham or silk. Their heads, indoor and out, are always picturesquely attired in bright blue silken Normandy caps.

The oldest citizens of this part of Pennsylvania still remember and speak of the wonderful broadcloths, flannels, blankets, Economy whiskey and wine they obtained from the Economites. The factories are all silent and deserted now, and the members have long since grown too feeble for hard labor. It was in Economy that silk culture and manufacture on a large scale were first begun in the United States.

The Simple Life They Lead.

Everything in Economy is run by rule and regulation much as at boarding-school. At 5 o’clock in the morning the bell on the one church rings and every one in the village rises. At 6 o’clock every dweller sits down to breakfast and what is eaten in one house is eaten in all. There is a day for “milk soup” and one for “wine soup” and for every other dish peculiar to the place. The bell rings again at 7 o’clock for all to go to work; at 9 it brings them back to lunch, at 12 to dinner, at 3 to lunch again, at 6 to supper, and at 9 it rings for everyone to put out his light and go to bed. No member ever rebels or disobeys.

There is a wine cellar in Economy famous for its old liquors, but it is never sold except to invalids. None of the Economites drink water, and their employees are given wine and cider. Visitors are all cordially helped to wine and cake, no matter how short their call.

How They Get Their News.

The only paper published in Economy is a novel one on wheels. It is the side of the milk wagon which carries to each dweller, as well as the milk, the work to be done. “The apples will be gathered to-morrow,” “The cherries will be gathered to-morrow,” or “Such a field will be reaped,” is inscribed on the wagon’s side, so that when all are supplied with their daily portion of milk they know what labor awaits them.

The store, post-office, hotel, church, town-hall and Rapp mansion are all situated near the centre of the village. The store is a strange-looking place, with little else than needles, thread and a few dishes for sale. Everything is bought and divided just the same as in a large family, even the carpet in one house is the same as in all the others.

No family names are used among the members, “Jacob” and “Anna” and “Dorothy” are sufficient. If there are two of a name, they distinguish them by the locality where they live. Thus, there are a “Dorothy near the mill” and a “Dorothy near the orchard.”

One laundry does the washing for the entire town. All the work is done now by employees, as the members have grown too feeble. The workers are obliged to obey every rule of the village. No man is allowed to smoke, chew or be intoxicated within town limits, and not one inhabitant is permitted to leave the village without first having obtained consent from their leader.

No Naps In Church Allowed.

On Sunday no excuse is accepted for absence from church. It is a quaint little chapel painted blue and white, and in keeping with the people who gather in it to worship according to their belief. There is no chance to forget prayers there while trying to see what others wear. Straight, uncushioned benches answer for pews. The men sit on one side of the church and the women on the other. Their leader, at present Mr. Henrici, selects a text from the Bible, and, sitting in a high-backed chair, tells his little band how they should live. He never writes out any long and eloquent sermon, but speaks as his heart believes, in a very simple but impressive manner. In the centre of the church is a clear space, with one lone bench. It is the “bench of punishment.” If anyone should be so unwise as to nod over the sermon or act otherwise than he should, Mr. Henrici calls him out to the “punishment bench,” where he must sit until service is over.

Miss Gertrude Rapp, the granddaughter of the founder, although at least eighty-six years old, still plays the organ and leads the singing twice every Sunday. She is yet a pretty woman, rather petite, has large blue eyes and the whitest of white hair, which, tucked under her quaint little blue Normandy cap, makes her a perfect picture of ye olden days. She occupies the Rapp house—the White House of Economy. It contains many costly, beautiful and curious relics. In the large parlor are vases filled with wax flowers and fruit which Miss Rapp made while a girl, and many other samples of her handiwork. There are two large square pianos, brought from Europe, and some costly paintings, among which is a copy of West’s “Christ Healing the Sick,” by Otis, with life-size figures, and “The Nativity,” by Andrea del Sarto. Among the stellar objects of interest is an escritoire, once the property of James G. Blaine’s mother, when she lived on the outskirts of Economy.

The Rapp garden is another beautiful spot. It is surrounded by a high, ivy-covered stone wall and is well-stocked with modern and ancient flowers. The only modern building near it is a costly green-house. Rising out of the centre of a lake is a bandstand and here on Sunday, during the summer months, the village band delights the citizens. Down near the corner is an ivy-covered grotto, built of a variety of stones, many of which were put there by the founder, George Rapp. A heavy door, covered still with the bark of the tree, keeps intruders out. The grotto is handsomely decorated on the inside. Set in the wall are four immense stones on each of which is inscribed:

When an Economite dies he is wrapped in a winding-sheet and buried in the white graveyard near the orchard. No tombstone ever marks his resting-place. In the centre of the orchard is a mound where the Indians buried their fallen after a battle with the French. Scientists have in value offered large prices to the Economites for the privilege of opening it, but they have an unusual regard for the dead, even though they were redmen.

Tramps Are Treated Like Princes.

The Economy Hotel has many visitors. One large room is always reserved for tramps. They are always treated just the same as the citizens. They are kept overnight, and, after being given some money in the morning, are started on their way. No one ever leaves Economy hungry.

The Economites dislike to be written about, because so many write to them afterwards and want to join them or come to their village, which is as private as any home. They absolutely refuse to take anyone. People often wonder what will become of their wealth, for they are very wealthy. Everything they engage in prospers, and it has become a saying that an Economite is always lucky. The Fort Wayne Railroad travels for miles through their property, and the society owns stock in both it and the Pittsburg and Lake Erie. The Economites were among the first to find valuable oil and gas on their land, and it is said they have more millions than members at present. Miss Rapp says she has never touched a penny since she was a baby, and that if she saw money she would not know a ten-cent piece from a dollar.

“I have all I can eat, all I can wear and I want nothing, so money is no use to me,” she said.

Romantic stories are often told by outsiders about the Economites. George Rapp had a stone chair hewn out of a high cliff overlooking a river at Harmony, upon which he used to sit and watch the men at work in the fields below, and in summer preach to his followers. The spot is still visited by sightseers and is known as “Rapp’s chair.” It is still well preserved.

The world does not seem nearer its end than it did when George Rapp founded his quaint society, yet his followers are firm in their faith that their last member will see its end. It will not be many years until his disciples will all have followed his footsteps through death’s grim portals, as they did through life, and then what will become of Economy and its millions?

Nellie Bly.