Saturday, March 21, 2020

The COVID-19 Pandemic has brought the entire globe to a standstill. When will this Pandemic end or more generically, how does a Pandemic end? The short answer – a pandemic ends when it runs out of victims.

Infectious diseases become Pandemics when they are spread across the globe via carriers of the infection – essentially humans.

Infectious diseases like the Spanish flu spread exponentially as more and more soldiers got infected during World War I and continued to get deployed across the globe. Gradually, as people develop immunities, receive vaccines, or otherwise shield themselves from infection, the pool of possible victims dwindles until the virus can no longer sustain itself.

Epidemiologists often describe the rate of infection in terms of a reproduction number, the average number of new people whom each sick person will infect. If this number is higher than one, even by a small amount, the disease is still spreading. (One study estimates that the reproduction number of the Spanish flu was 1.49 when the disease first hit Geneva and a whopping 3.75 in the second wave, which came shortly thereafter). If the number is less than one, the disease is on the decline.

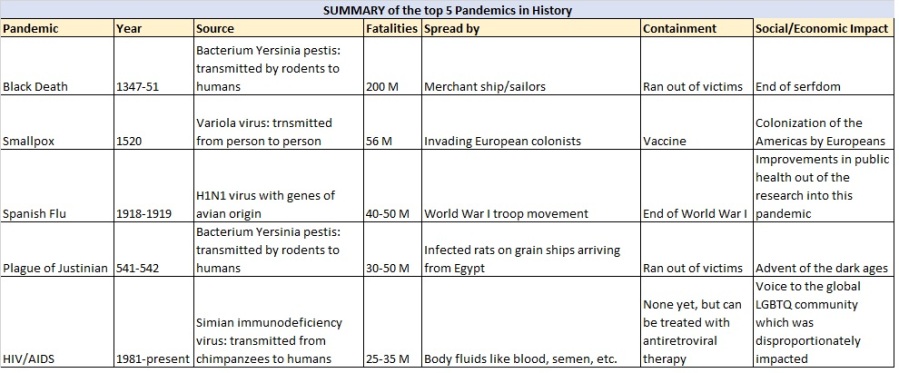

So let us look at some of the deadliest Pandemics in history and look for any patterns and lessons:

The Black Death (Bubonic Plague) (1347-1351)

The Black Death was a devastating global epidemic of bubonic plague that struck Europe and Asia in the mid-1300s. The plague arrived in Europe in October 1347, when 12 ships from the Black Sea docked at the Sicilian port of Messina. People gathered on the docks were met with a horrifying sight: most sailors aboard the ships were dead, and those still alive were gravely ill and covered in black boils that oozed blood and pus. Sicilian authorities hastily ordered the fleet of “death ships” out of the harbor, but it was too late: Over the next five years, the Black Death would kill more than 20 million people in Europe – almost one-third of the continent’s population.

However, Europeans were scarcely equipped for the horrible reality of the Black Death. Blood and pus seeped out of these strange swellings, which were followed by a host of other unpleasant symptoms – fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, terrible aches and pains – and then, in short order, death. Today, scientists understand that the Black Death, now known as the plague, is spread by a bacillus called Yersina pestis, named after French biologist Alexandre Yersin who discovered it at the end of the 19th century. The bacillus travels from person to person pneumonically, or through the air, as well as through the bite of infected fleas and rats. Both of these pests were particularly prevalent aboard ships of all kinds – which is how the deadly plague made its way through Europe – one port city after another.

After Messina, the Black Death spread to the port of Marseilles in France and the port of Tunis in North Africa. Then it reached Rome and Florence, two cities at the center of an elaborate web of trade routes. By the middle of 1348, the Black Death had struck Paris, Bordeaux, Lyon and London.

The Black Death is estimated to have killed 30% to 60% of Europe’s population. In total, the plague may have reduced the world population from an estimated 475 million to 350–375 million in the 14th century. It took 200 years for Europe’s population to recover to its previous level and some regions like Florence only recovered by the 19th century.

The most visible impact of this pandemic was the end of serfdom. Before the plague, peasant serfs were confined to their lord’s estate and received little or no payment for their work. Overpopulation and shortage of resources led to malnutrition and extreme poverty for many peasants. After so many people died, serfs were free to move to other estates that provided better conditions and receive top pay for their work. Landowners, desperate for their labor, often provided free tools, housing, seed and farmland. The worker farmed all he could and paid only the rent.

Eventually two popular uprisings, La Jacquerie in France in 1358 and the Peasant’s Revolt in England in1381 followed the Black Death. Although the social and economic effects of the plague were not the primary cause for the downfall of feudalism and the rise of a mercantile class, most historians agree the Black Death contributed to it.

Smallpox (1520):

Smallpox is thought to have originated in India or Egypt at least 3,000 years ago. The earliest evidence for the disease comes from the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses V, who died in 1157 B.C. His mummified remains show telltale pockmarks on his skin.

The disease later spread along trade routes in Asia, Africa, and Europe, eventually reaching the Americas in the 1500s. In February of 1519, the Spaniard Hernán Cortés set sail from Cuba to explore and colonize Aztec civilization in the Mexican interior. Within just two years, Aztec ruler Montezuma was dead, the capital city of Tenochtitlan was captured and Cortés had claimed the Aztec empire for Spain. Spanish weaponry and tactics played a role, but most of the destruction was wrought by an epidemic of smallpox that gradually spread inward from the coast of Mexico and decimated the densely populated city of Tenochtitlan in 1520, reducing its population by 40 percent in a single year.

Indigenous populations in the Americas had never experienced the disease before the arrival of Spanish and Portuguese explorers in the late 15th Century and thus had no immunity. Deadly smallpox pandemics raged through Mexico and Central America in the 1520s. All the diseases brought (unintentionally) by the explorers are thought to have led to a reduction in native populations of up to 90 percent.

Smallpox is caused by an inhaled virus, which causes fever, vomiting and a rash, soon covering the body with fluid-filled blisters. These turn into scabs which leave scars. Fatal in approximately one-third of cases, another third of those afflicted with the disease typically develop blindness.

The ability of smallpox to incapacitate and decimate populations made it an attractive agent for biological warfare. In the 18th century, the British tried to infect Native American populations. One commander wrote, “We gave them two blankets and a handkerchief out of the smallpox hospital. I hope it will have the desired effect.”

The pandemic was finally brought under control through a vaccine by Dr. Edward Jenner. Jenner had noted that milkmaids, among others, who caught the cowpox from their animals rarely sickened with smallpox and resolved to test cowpox as a protection against smallpox. Jenner took material from a dairymaid’s cowpox and introduced it into scratches on an eight year old boys’ arms. He thus invented “vaccination” — a word whose root comes from the Latin for cow. Subsequently, mass vaccination against smallpox got going in the second half of the 1800s. And in 1980, the WHO declared smallpox eradicated.

Spanish Flu (1918-1919):

The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic infected 500 million people worldwide and killed an estimated 20 million to 50 million — that’s more than all of the soldiers and civilians killed during World War I combined.

While the global pandemic lasted for two years, the vast majority of deaths were packed into three months in the fall of 1918. Historians now believe that the fatal severity of the Spanish flu’s “second wave” was caused by a mutated virus spread by wartime troop movements.

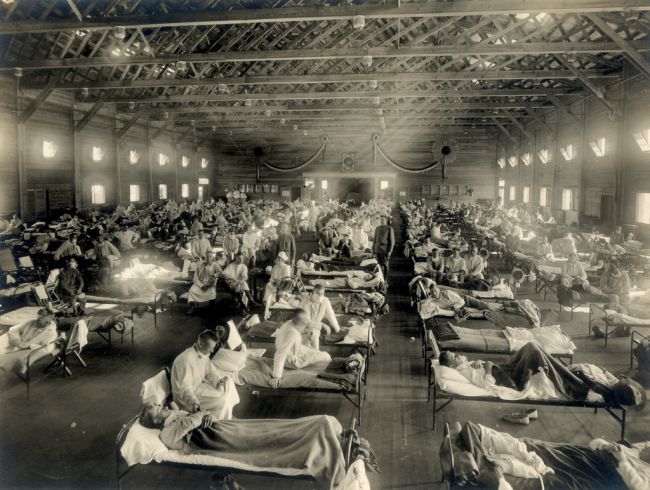

When the Spanish flu first appeared in early March 1918, it had all the hallmarks of a seasonal flu, albeit a highly contagious and virulent strain. One of the first registered cases was Albert Gitchell, a U.S. Army cook at Camp Funston in Kansas, who was hospitalized with a 104-degree fever. The virus spread quickly through the Army installation, home to 54,000 troops. By the end of the month, 1,100 troops had been hospitalized and 38 had died after developing pneumonia.

As U.S. troops deployed for the war effort in Europe, they carried the Spanish flu with them. Throughout April and May of 1918, the virus spread like wildfire through England, France, Spain and Italy. An estimated three-quarters of the French military was infected in the spring of 1918 and as many as half of British troops. Luckily, the first wave of the virus wasn’t particularly deadly, with symptoms like high fever and malaise usually lasting only three days, and mortality rates were similar to seasonal flu.

Interestingly, it was during this time that the Spanish flu earned its misnomer. Spain was neutral during World War I and unlike its European neighbors, it didn’t impose wartime censorship on its press. In France, England and the United States, newspapers weren’t allowed to report on anything that could harm the war effort, including news that a crippling virus was sweeping through troops. Since Spanish journalists were some of the only ones reporting on a widespread flu outbreak in the spring of 1918, the pandemic became known as the “Spanish flu.”

But, somewhere in Europe, a mutated strain of the Spanish flu virus emerged that had the power to kill a perfectly healthy young man or woman within 24 hours of showing the first signs of infection. In late August 1918, military ships departed the English port city of Plymouth carrying troops unknowingly infected with this new, far deadlier strain of Spanish flu. As these ships arrived in cities like Brest in France, Boston in the United States and Freetown in South Africa, the second wave of the global pandemic began. The World War I troop movement proved to be the carrier of this flu. The most bizzare was the mode of death – struck with blistering fevers, nasal hemorrhaging and pneumonia, the patients would drown in their own fluid-filled lungs.

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas. (Image credit: Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine)

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas. (Image credit: Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine)Decades later this phenomenon was known as “cytokine explosion.” When the human body is being attacked by a virus, the immune system sends messenger proteins called cytokines to promote helpful inflammation. But some strains of the flu, particularly the H1N1 strain responsible for the Spanish flu outbreak, can trigger a dangerous immune overreaction in healthy individuals. In those cases, the body is overloaded with cytokines leading to severe inflammation and the fatal buildup of fluid in the lungs. British military doctors conducting autopsies on soldiers killed by this second wave of the Spanish flu described the heavy damage to the lungs as akin to the effects of chemical warfare.

The core reason for the rapid spread of Spanish flu in the fall of 1918 was the public health officials unwilling to impose quarantines during wartime. The public health response to the crisis in the United States was further hampered by a severe nursing shortage as thousands of nurses had been deployed to military camps and the front lines. The shortage was worsened by the American Red Cross’s refusal to use trained African American nurses until the worst of the pandemic had already passed.

By December 1918, the deadly second wave of the Spanish flu had finally passed, but the pandemic was far from over. A third wave erupted in Australia in January 1919 and eventually worked its way back to Europe and the United States. It’s believed that President Woodrow Wilson contracted the Spanish flu during the World War I peace negotiations in Paris in April 1919.

The mortality rate of the third wave was just as high as the second wave, but the end of the war in November 1918 removed the conditions that allowed the disease to spread so far and so quickly. Global deaths from the third wave, while still in the millions, paled in comparison to the apocalyptic losses during the second wave.

The pandemic revealed just how many lives can be saved by social distancing: Cities that cancelled public events had far fewer cases. Just as the outbreak was unfolding, Philadelphia threw a parade with 200,000 people marching in support of the World War I effort; by the end of the week, 4,500 people were dead from the flu. Meanwhile, St. Louis shuttered public buildings and curtailed transit; the flu death rate there was half of Philadelphia’s.

The flu affected 28% of all Americans and claimed the lives of an estimated 675,000. The US industrial production and wider business activity dipped at the height of the pandemic in Oct 1918.

COVID-19 and Containment:

So there are 3 factors in play during an epidemic – the source, the containment and the vaccine.

In our rapidly shrinking and well connected world, containment of an epidemic becomes difficult. So it is extremely important to report the emergence of a new virus/illness in a timely fashion and even more important, is to react to the report and build defensive measures against the new virus/epidemic.

In case of COVID-19, we fell short on both counts. First, China underwent denial for more than a month (see Timeline) after the new virus was first reported in Wuhan, going to the extent of reprimanding the medical professionals who reported it. This behavior by a global superpower and a permanent member of the UN Security Council is utterly disgraceful!

The second failing was the rest of the world not implementing defenses against the virus in time. Even now, a lot of countries do not have adequate testing infrastructure to determine the blast radius of the virus in their respective countries.

So while we wait for a vaccine to be developed and approved – a few are already in clinical trials, our best bet is isolation/quarantine to cutoff any new targets for the virus. And the biggest hope is that governments across the globe and WHO are better prepared to deal with the next Pandemic.

A great example of an epidemic contained timely, is the SARS epidemic of 2003. SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) incidentally, is an illness caused by one of the 7 coronaviruses that can infect humans. In 2003, an outbreak that originated in the Guangdong province of China, rapidly spread to a total of 26 countries, infecting just over 8,000 people and killing 774 of them.

But the impact of the SARS pandemic were largely limited due to an intense public health response by global authorities, including quarantining affected areas and isolating infected individuals. Here too, China took its own sweet time to report it to the world and various health organizations and it is high time that this issue is resolved though intelligent monitoring of new illnesses across the globe. We cannot continue fighting pandemics in the 21st century, using 19th century techniques.