Thursday, December 5, 2024

Only two visual artists were blacklisted for their alleged Communist sympathies during the Red Scare of the 1950s: Rockwell Kent (1882-1971) and William Gropper (1897-1977).

Subpoenaed by Republican Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in 1953, Kent — who had faced the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1939, and whose passport was revoked in 1950 — defended himself while refusing to answer the question about Communist Party membership. Appearing earlier that year, Gropper, who (like Kent, by most accounts) was not and had not been a party member, pleaded the Fifth.

Ironically, the work that raised a red flag, so to speak, was Gropper’s “America, Its Folklore” of 1945, one of seven paintings in the Phillips Collection exhibition “William Gropper: Artist of the People,” on view through Jan. 5.

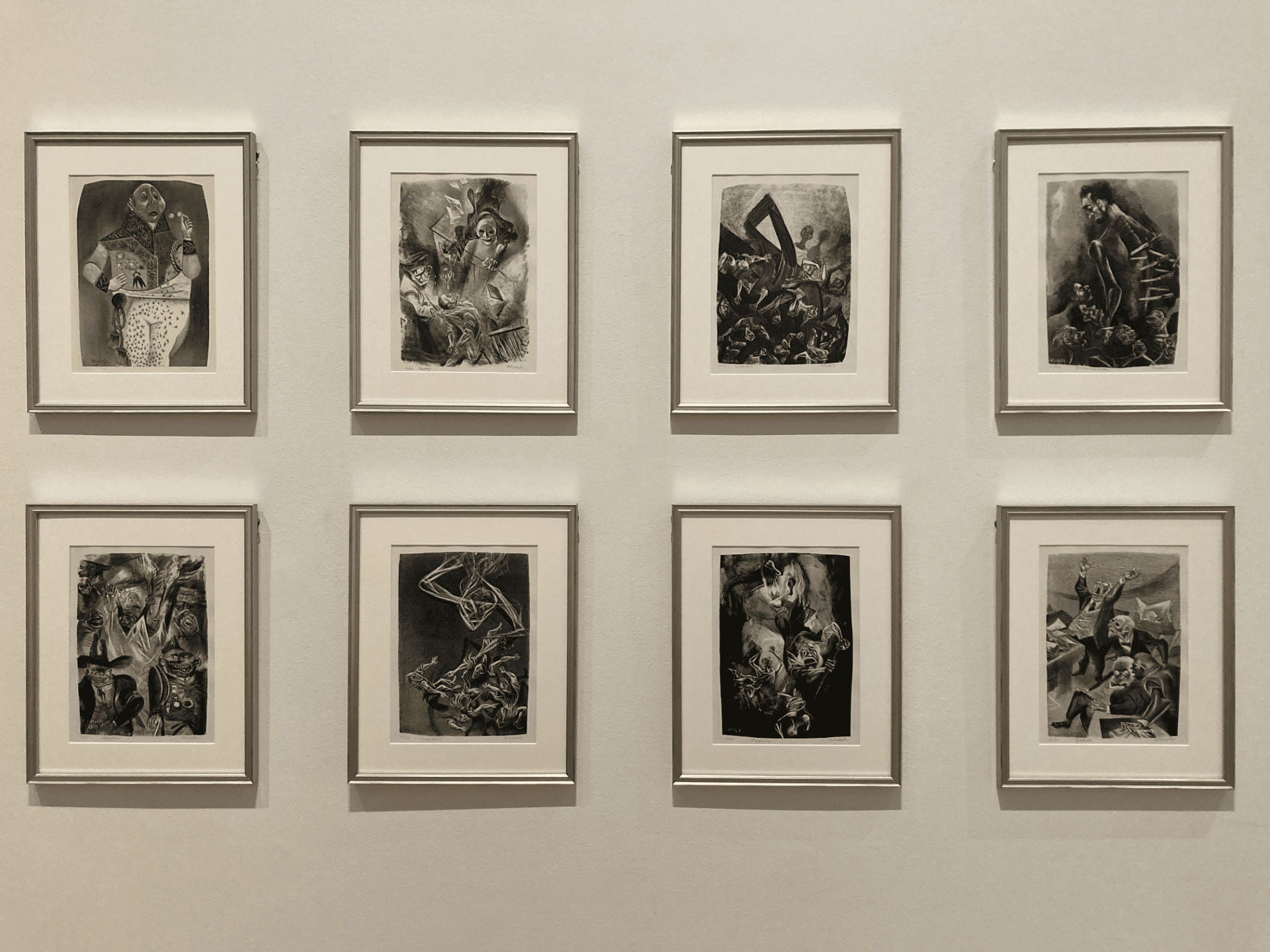

Installation view of eight works from the “Capriccios” series, 1953-57. William Gropper. Photo by Richard Selden.

Largely drawn from the collections of Craig Gropper, the artist’s grandson, and of trustee emeritus Harvey Ross (whose great-aunt was Gropper’s mother) and Ross’s late wife Harvey-Ann, the exhibition features numerous works on paper, mostly cartoons Gropper drew for mainstream as well as radical and Yiddish publications.

Gropper’s painted map — oddly bringing Jasper Johns to mind — is densely filled with schoolbook-style illustrations: a witch on a broomstick near Salem, Massachusetts; Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox in Minnesota; John Henry, sledgehammer held high, in Alabama; Frankie with a gun still pointed at her (supine) man, Johnny, in Missouri; Mark Twain’s jumping frog in Calaveras County. Reproduced for State Department distribution to U.S. outposts abroad, it became Exhibit A in the subcommittee’s cross-examination. (The original hung in Craig Gropper’s childhood bedroom.)

Raised on New York’s impoverished Lower East Side by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, Gropper was committed to battling social and economic injustice. Socialist and anti-fascist, yes, but anti-American he was not. One wall in the Phillips exhibition is devoted to his monumental 1945 painting, 14 feet tall, of a tanned and grinning Bunyan. Towering over un-Minnesota-like snowcapped mountains, the lumberjack of legend is a symbol of American might.

When the Cranbrook Academy in suburban Detroit canceled an exhibition of work by the newly blacklisted Gropper, he convened a show in a private home, vowing to fight back with a no-holds-barred series modeled on Francisco Goya’s late-18th-century “Caprichos” series.

Titled “Capriccios,” Gropper’s portfolio of 50 lithographs — “on the Inquisitions of our time,” in his words — were created between 1953 and 1957. Eight of these extraordinarily dark (in both senses) works, the most complex and powerful in his oeuvre, in which Gropper goes toe-to-toe with George Grosz if not Goya, are displayed in two rows of four: “Pomp,” “Justice,” “Blacklist” and “Emancipation”; and “Patrioteers,” “Informers,” “Vengeance” and “Politicos.”

With Expressionist figures similar to those of “Politicos,” the much earlier, Max Beckmann-like “Eternal Senator” of 1935, the year after Gropper went to Washington on assignment for Vanity Fair, hangs on the wall opposite “Paul Bunyan.” Intricately composed and incorporating Cubist touches (a glass pitcher and water glass on a tilted desk), the painting exemplifies Gropper’s bold use of color. Large primary-color patches divide the canvas vertically: yellow for the dome, blue for the senator’s jacket, red for the carpet.

“Artist of the People” includes one book, “The Illustrious Dunderheads” of 1942. Edited by ACLU activist Rex Stout, author of the Nero Wolfe detective novels, the book’s illustrations by Gropper mocked isolationist members of Congress, whose records of voting against the Roosevelt administration were provided along with damning quotes.

In this vein, the cartoon “We’re Just Crazy About Fascism,” circa 1940, depicts isolationist politicians and celebrities — including William Randolph Hearst, Charles Lindbergh and Ezra Pound — singing with fervor; Pound holds a “hymnal” titled “Mein Kampf.”

As a Jew, Gropper took isolationism personally. His 1943 drawing, “The Murderers Spill Our Blood,” is displayed with the caveat: “This image may be upsetting or evoke distressful emotions.” Responding to the Nazi massacre of the Czech village Lidice, it appeared in several publications including Morning Freiheit, where it was accompanied by a statement by Gropper that read in part (translated from the Yiddish): “I cannot remain silent and watch as my Jewish brothers and sisters are murdered. I want to protest, scream, fight and save the lives of the Jewish people.”

The label for “Hirohito Composed a ‘Peace Poem,’ Tokyo Reports,” a Morning Freiheit cartoon of 1938, has both the “may be upsetting” caveat and this commentary: “Gropper employed grotesque and pervasive racist stereotypes — slanted eyes, buck teeth and coke-bottle glasses — in his caricature of Hirohito that contributed to a culture of racism against Japan while simultaneously offering scathing indictment of his militaristic imperialism.”

“Automobile Industry,” 1940-41. William Gropper. Photo by Richard Selden.

These and other editorial cartoons in the exhibition show Gropper to be as skillful, if perhaps less subtle, a draftsman as the best-known cartoonists of the era, such as Bill Maudlin and Herblock (not to mention Dr. Seuss). That they greatly outnumber the paintings may have been intended as a wake-up call. At an Oct. 27 exhibition-related event, videotaped and posted on YouTube, lender Ross remarked: “What better time than at this moment of great peril to all that we hold dear?”

Three of the paintings on view are studies for social-realist murals from the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The picture-book snow scene, “Suburban Post in Winter,” circa 1936-37, relates to a work in the Freeport, Long Island, post office. As horizontal as “Suburban Post” is vertical, “Construction of the Dam” of 1938 was painted in preparation for a dramatic mural (still to be seen at the Department of the Interior) in which Gropper “integrated” the racially segregated work crew. A Guggenheim Fellowship had enabled Gropper to take a cross-country trip on which he visited the Hoover (Boulder, at the time) and Grand Coolee Dams. The most striking of the three, “Automobile Industry” of 1940-41, is a study for a Detroit post office mural now at Wayne State University.

Though he never received an official apology for his blacklisting, Gropper’s career revived and he stayed prolific (and satiric) to the end. “Self-Portrait” of 1965, from Craig Gropper’s collection, shows the white-haired artist in profile as — grinning with malicious satisfaction — he completes the face of his latest target in blood-red ink.

William Gropper: Artist of the People

Through Jan. 5

The Phillips Collection

1600 21st St. NW

phillipscollection.org

202-387-2151